With droughts, floods and bushfires becoming regular occurrences, how should investors prepare their portfolios to face growing water stress? Mark Dunne takes a look.

Single-use plastic has become the great pariah of our time. The chemicals it emits when discarded in towns, cities, the countryside and the oceans, pollutes our planet and is a danger to wildlife.

It is such a big topic with consumers that former prime minister Theresa May set a target to eradicate disposable packaging in the UK within 25 years. David Attenborough has made a documentary about it, while Prince Charles has given speeches on the dangers that the humble plastic bag poses to the environment. Even Greenpeace has a dedicated team to campaign on the issue.

That’s fair enough. The chemicals used in making plastic harm the environment, but perhaps people should be equally, if not more, concerned by the water inside the plastic bottle .

As bad as single-use plastic is for the environment, countries are unlikely to declare war on their neighbours over plastic bags floating in the sea. Yet they might if the source of water they share with other countries is diminishing and their people are thirsty. Indeed, wars where water has been a factor behind the hostilities have been fought and the term “water conflict” could enter the lexicon in the coming years as populations grow and lakes and rivers shrink.

Water crisis has been named as the world’s leading global risk by the World Economic Forum, which has judged the issue a greater threat to humanity than food shortages or infectious diseases. Water stress has even been at the heart of a James Bond film. In 1965, the secret agent was trying to recover stolen nuclear bombs in Thunderball, but by 2008’s Quantum of Solace weapons of mass destruction had been replaced by a man trying to restrict access to water. A worrying sign of things to come.

Water, water everywhere…

Not all water is the same. It covers three-quarters of our planet, but only 3% is freshwater, which is the stuff we drink, bathe in, clean our clothes with and spray on crops. This is found in glaciers, ponds, lakes, reservoirs, rivers, streams and wetlands as well as underground. The rest is saltwater that makes up the seas and oceans and those of us who have taken mouthfuls of it on trips to the beach will understand why we don’t use it to make coffee.

Of the water that is fit for consumption, 70% is underground and 29% is frozen in the polar caps leaving just 1% for personal use. Of that 1%, around nine cups in every 10 are used by commercial enterprises, including farms.

The biggest problem is that water is of finite supply, so huge population growth projections do not make good reading. One area where we could see increasing stress in the coming years is Asia. Around 60% of the global population lives there, but the continent only has 33% of the world’s freshwater, according to Citibank.

At the time of writing, science has not worked out an economically viable means of making H2O, so as populations grow the water shortages witnessed in California and South Africa in recent years will become more prevalent.

Another problem is that of existing sources of drinking water being lost to pollution and leakage. The United Nations (UN) estimates that more than 80% of wastewater, including human waste, is sometimes discharged into rivers without being cleaned first. Burst pipes and leaking taps are also a concern. “Water is vital to the functioning of the global economy, but climate change, pollution and increasing industrialisation is putting a lot of pressure on this finite resource,” warns Emily Chew, global head of ESG at Manulife Investment Management.

“We don’t have enough water in the world for all the current rates of growth in global population and industrial activity, and then what we do have is being increasingly polluted,” Chew says.

A material issue

Investing in companies that increase access to water or improve its quality is not just for people who are driven to make the world a better place. Water is a material issue for those investing in mainstream businesses, too.

Water stress is not just something that affects people in other parts of the world. A lack of clean water can hit economic growth globally.

Indeed, the UN puts the annual economic loss related to water insecurity, inadequate supply, poor sanitation and flooding at $470bn (£359.5bn). It warns that such problems could knock 6% off the value of the global economy in the next 30 years.

Water is needed to grow food, to generate energy and to keep offices, factories, warehouses and shops open. Indeed, the UN estimates that three in every four jobs globally are, to some extent, dependent on water.

This is an issue that governments cannot solve alone. Private capital is needed to improve the quality of water, stop leakages and increase consumer access to it. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development estimates that a $22.6trn (£19.1trn) investment will be needed by 2050.

It is in investors’ interests to help solve this issue. If companies cannot get access to the water they need, their business could suffer. Misusing the resource could also count against them. “Mis-management of water can have an impact on a company’s balance sheet and the profit and loss as well as its reputation,” says Edward Geall, a thematic research analyst at Newton Investment Management.

Ways to play

Demand for freshwater is expected to rise. The UN believes that we will have to share the planet with 9.7 billion other people by 2050, which is almost 2 billion more citizens than we have now. This will be felt most in major towns and cities as urban populations are projected to reach 6.3 billion in the next 30 years, up from 3.4 billion in 2009.

So the infrastructure on how water is stored, transported and delivered will need to be upgraded. Solutions will also have to be found to deal with the resulting rise in wastewater.

Tech companies will have to play their part, especially in preventing leaking taps and bursting pipes. According to a Consumer Council for Water report in 2017, 3.1 billion litres of water was lost on the way to homes and businesses in England and Wales every day due to leakage, so how much must be lost in developing markets?

Purifying wastewater, improving distribution, developing products that are more efficient in their use of water, such as meat-free meat, and products that ensure its security are ways investors can gain exposure to the long-term water trend.

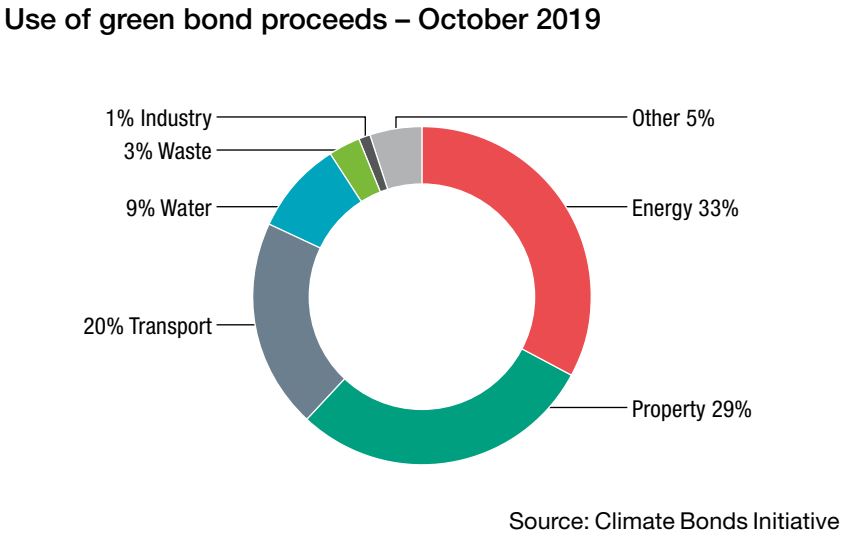

The amount of private capital raised by companies to fund projects that protect the environment is at an all-time high, if the green bond market is a gauge of institutional appetite. Yet water does not appear to be high on institutional investors’ list of priorities, being the fourth most popular reason to issue such debt.

Less than 10% of the $202.2bn (£154.6bn) green bond market has been used to fund water projects, far behind those for energy, property and transport (see above).

Where’s the risk?

RobecoSAM was an early innovator in this area. It launched what it claims was the world’s first pure water fund in 2001.

“Back then we realised that water is a key issue, not just for the economy but society in general,” says Roland Hengerer, senior analyst, sustainable investing research at RobecoSAM. “There was an opportunity in that as water becomes more important over time companies providing services, technologies and infrastructure for it will have a bright future.”

The RobecoSAM Sustainable Water Fund, which is now worth €1.38bn (£1.16bn), was established to back companies that are working to address the resource’s quantity, quality and allocation. It regularly beats its benchmark. In the past year the fund returned almost 32% and has grown 7.35% since inception. “Looking back, launching the fund was a good decision,” Hengerer says.

The fund focuses on four areas: utilities, water infrastructure, chemicals, and quality or analytics. This gives it a small universe of stocks to pick from, so management consider companies that make at least 20% of their revenue from water. Agilent Technologies, Suez, Veolia and Thermo Fisher Scientific are all on its top 10 holdings list.

The sectors it is most exposed to are industrials (39.2%), healthcare (19.3%), utilities (17.1%) and discretionary consumer (8.6%).

Water funds appear to be enjoying a moment in the sun as BNP Paribas Aqua also enjoyed similar success last year. It returned 33% in 2019, a sign perhaps that demand is rising for the services of companies in the water market.

Manulife also assesses a company’s water risk before investing. In terms of ascertaining if water can affect a company’s valuation, reputation or revenue, the firm looks at the sources on which it relies. If it is assessing a food and beverage company, for example, is it operating in China? If so, are their plants in areas where there is water stress and competition for water with the agriculture sector.

Or, if it is a semi-conductor company, does it have pre-fabrication plants in California, which is a water-stressed region of the US, or in Taiwan which does not suffer from such issues. “When information about the location of company operations is available, we can then map these assets to water basins to form an assessment of risk,” Chew says.

Manulife then looks at the company’s water efficiency rate, a task made easier if it has disclosed the average number of water gallons used to generate a unit of production. What is the trend in their water use? Is it becoming more efficient? Can it demonstrate a strategic approach to water, such as establishing a board-level sustainability committee that sets water targets? Are those targets linked to management incentives? Do they have evidence of a strategic approach to make the business water resilient, such as recycling or using greywater (from baths, sinks and washing machines)?

But the firm believes that to understand truly how much water a business uses and where it is sourcing it from, you need to also look at its supply chain.

Engagement is, of course, a big part of sustainable investing. For example, having invested in a food and beverage company in China, which is dependent on a particular water basin, Manulife requested greater clarity on how the company manages water risk.

Following the discussions, the company has regularly disclosed such data, and has shown a 10% fall in water consumption. “We raise this issue with companies because a water shortage would affect their ability to make products, either directly or through procuring inputs from their supply chain,” Chew says.

Manulife also engaged with a US electric utility that was dispersing the coal ash from its energy generation process into wastewater ponds. As the climate effect is making rain and flooding more frequent, there was a risk that these ponds could overflow and contaminate the local water supply. The company has since signed an agreement to improve how it manages its wastewater pond.

The physical risk of climate change has a strong link to water issues.

Roland Hengerer, RobecoSAM

Water is not just an issue for equities. It is a part of real assets too. In Manulife’s real estate projects, for example, it has a degree of control over water efficiency measures and is being innovative in how it sources and uses water.

Manulife has also been harvesting the rain. In a pilot project in Montreal it has used rainwater to grow vegetables. “Water is a big part of how buildings operate,” says Maria Clara Rendon, ESG director of private markets at Manulife Investment Management.

“One of the reasons why water is different to other resources is that it is sensitive for communities,” she adds.

Rendon says that this is an important aspect that a business needs to get right. “If water is not managed properly it may put a company’s licence to operate at risk.”

A big element of this is serving the communities in which companies operate to ensure that they are not drawing too much from dwindling resources. In California, a Manulife project is managing a river co-operatively to irrigate farmers’ crops and recharge groundwater. “It is about communities sharing resources,” Rendon says.

Thirsty industries

So it is not just people who need water; it is vital for companies too. Before we start naming and shaming the industries that use more than others, an important distinction has to be made. “There is a difference between water withdrawal and water consumption,” Hengerer says, before explaining that utilities are the largest withdrawers of water to cool their power plants, which is discharged back into rivers and oceans once it has been used.

This is another example of water and climate issues being so closely intertwined. “We have had cases in Europe where the summers were so hot that some nuclear power stations reduced their output because the cooling water would have increased the already high water temperature above acceptable thresholds,” Hengerer says.

Consumption is the area where improvements can be made. Miners, the chemical industry, paper producers, food and beverage companies and semi-conductor makers are huge consumers of H2O, but agriculture, Hengerer claims, is by far the biggest consumer of water, stating that it uses 70% of the world’s freshwater, according to the UN Food & Agriculture Organisation.

“This is not coming from companies, but often from small farmers so it is difficult to handle,” he adds. Geall goes a step further, believing that it is not just the amount that industry uses that is the problem. “It is also shamefully lagging in its usage practises; not only is it using a lot, it is also wasting a hell of a lot too,” he says.

He labels irrigation techniques used in farming as being inadequate for today’s standards. “Irrigation methods are resulting in poor crop yields, and huge amounts of water being wasted. “Rather than targeting where the water goes and delivering the right amount, what we are seeing is an outdated flood-irrigation technique being used,” Geall adds.

The textile industry is another sizeable consumer of water, due to water use in the production of cotton.

Manulife looks closely at textile companies, to find out where they source their cotton.

“Cotton is a thirsty crop,” Chew says.

“We look at water consumption from a risk perspective, but we also see that scarcity can create opportunity for companies to increase supply, make industrial processes more efficient, or improve water quality,” Chew says.

More understanding of what it takes to get a shirt onto a high street store’s shelves could motivate companies to think about how they are using raw materials.

“There is not enough understanding on the part of the consumer as to where their products are coming from, especially in the fast fashion sector,” Geall says.

Data drought

Around 2.5 billion people do not have access to clean drinking water and more than 4 billion of the globe’s 7.5 billion citizens are without safe sanitation. “That strikes me as an incredible thing to remedy, but we are not having the discussion on the importance of remedying these issues in the way that we are with plastic, for example,” Geall says.

“Water has not quite achieved the same level of prominence among investors as the more familiar sustainable topics, such as reducing C2O emissions, but it is starting to enter the discourse a little bit more.

“Investors understanding the importance of water and the impact that it has on our everyday lives is based on data, but in this case, the data is not quite as developed as other areas of the sustainability debate,” he adds.

Robert-Alexandre Poujade, an ESG analyst at BNP Paribas Asset Management, says that clients have less focus on water conservation because “the entry door of ESG” has been climate change.

“The big push around ESG has started on the environmental side, especially climate,” he adds. “Water is lagging a little, but it is obvious that it is next in terms of awareness from our clients and from the financial community.”

Another reason for this could be the lack of credible and recurring information, which is needed to hook in consumers and therefore company boardrooms.

“One of the key drivers of consumer adoption of plant-based diets has been the environmental impact,” Geall says. “As well as the carbon footprint there is the water footprint. The amount of water needed to produce beef relative to a plant-based substitute is significantly greater. Consumers are starting to pay attention to that, but they are only able to do that if they have the information at hand.”

Mis-management of water can have an impact on a company’s balance sheet and the profit and loss as well as its reputation.

Edward Geall, Newton Investment Management

This is what Poujade is working to achieve. “Our role is to push for transparency on water risk that companies are facing because there are gaps in corporate disclosure.

“The dream for us is to have more visibility on how much water companies are taking and how much wastewater they are producing.”

Newton has a dedicated responsible investment team assessing the sustainability of water on a sectorial and at the individual security level. “We have to be honest, if the industry looks at water data and how we can use it to gauge impact verses something like carbon, the underlying data is not as advanced as we would like it to be,” Geall says.

This is strange as it is intertwined with one of the world’s biggest environmental issues.

“Climate change is often all about water,” says Hengerer. “The physical risk of climate change has a strong link to water issues.

“Many of the negative issues that come from rising global temperatures are connected to water and changes in the hydrological cycle, for example, either more droughts, and from that you have forest fires, or too much water with flooding and too much rainfall.”

It appears that there are those who understand that there is a link between the two. “Some investors think about the issue as a climate-water nexus,” Chew says. “As the climate changes, the way the environment interacts with water changes radically too, in that there’s too much water in some places or not enough in others.

“The water table can also shift as you put it under stress from industrial and residential use,” she adds.

“There is a lot of attention globally on climate change,” Chew says. “If you fully understand the climate issue then you will know that it is also about water because they are closely tied together.”

Perhaps the problem is that in some developed nation countries it has always been there.

“Water is taken for granted in our culture,” Chew says. “Plastic on the other hand is material and we can decide whether to use it or not. We can see how much plastic recycling we gather each week, so perhaps plastic is more tangible in our material culture.”

The size of the challenge of ending water stress might also be putting people off. “Islands of plastic floating in the sea is a smaller scale problem than water scarcity, so perhaps people feel that they can provide a solution for it,” Rendon says.

Global problem, local issue

Despite its importance to our lives and the planet, water does not have as high a profile in the news as other sustainable issues, such as climate change and single-use plastics.

“Water is present in almost all issues that we face today, but it may not always be the big key word or make the headlines,” Hengerer says.

Perhaps the reason why the City has warmed more to climate change is because a market has emerged for it.

“Climate change has been an easier issue for the finance sector to get its head around because carbon emissions are by their nature global, so it has been easier to measure and model it globally and, therefore, to disseminate that knowledge to investors.

“Water scarcity on the other hand is very location based and so it’s difficult to get data to enable you to roll out assessments of risk and impact at scale across large portfolios,” she adds.

Generating interest and action here may have to come from the highest level. Hengerer wants governments to do more to promote water conservation in the way that they are working to fight climate change. “Governments have a strong role to play,” Hengerer says. “They can set strict regulation on water quality and efficiency and have the power to set water tariffs to promote conservation and reduce consumption.”

Newton’s Geall also believes that many environmental challenges, especially water, need to see greater levels of government intervention.

“The electric vehicles debate, and the impact of the internal combustion engine is slowly influencing consumers to reassess what vehicles they want to buy,” he says. “If governments imposed restrictions on water usage, or the US imposed a water tax on the agricultural sector, it would be a powerful step towards not only increasing understanding, but conserving the resource itself.”

Local governments are buying back water utilities with Paris and Berlin taking such steps to control it. “Single-use plastic has the top position on many peoples’ agenda, but these cases show that water is at the top of governments’ agenda,” Hengerer says.

Berlin and Paris are not the only areas where the authorities are taking control.

In Asia, the huge supply/demand imbalance has meant that governments are having to step in. “In Asia there is a concern about water running out and blocking economic growth,” Chew says. “Regulators in that region are considering all kinds of interventions, whether it is putting a market price on water, offering subsidies for efficiency or increasing supply mechanisms.”

Chew’s colleague Rendon believes that local people can have a powerful voice when it comes to motivating their leaders. “Community pressure cannot be underestimated,” she says. “It has been a deal-breaker for some companies, who have closed operations due to conflicts with local communities. If that pressure translates into government action that might be a way to increase water conservation.”

People power and government intervention is one thing, but science will be crucial in eradicating water stress.

Unless economically-viable technology emerges that can turn saltwater into freshwater or collect moisture from the air or make H2O out of base materials, then we are stuck with a finite resource that will have to meet rising demand.

Raising more awareness of the issue among consumers and influencers would be a good start.

Matt Damon, star of the Jason Bourne films, is doing his bit by co-founding a charity that works to improve access to clean water, but he cannot pull in the crowds like Swedish climate change campaigner Greta Thunberg.

It seems that water needs a champion and fast.