Once upon a time America was a true outlier. This applied to not only its values, but the very essence of its unique political system and the power of its markets, which are reflective of Uncle Sam’s economic might.

This unique nature fed positively through all facets of society: from your everyday Joe to the plebian and aristocratic classes alike. America equalled opportunity like no other country and everyone benefitted. That, if it was true, is no longer the case.

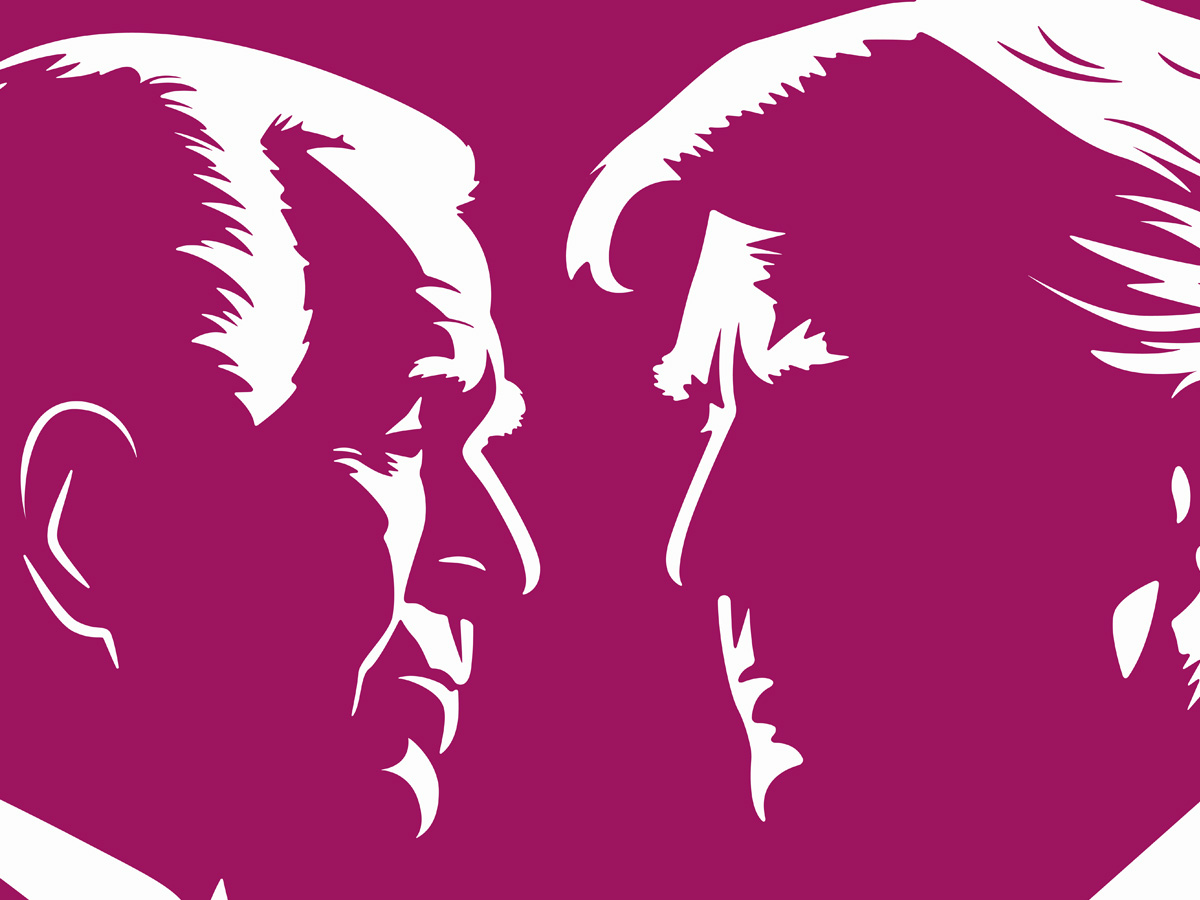

The decline and fall of America is evident in its potentially destructive divisiveness. But the trouble with America is not in its explosive news headlines. The picture is potentially far worse – partly because the doom is working on a number of levels.

Take the investor outlook as an example.

For investors, America was once a dead cert, but the picture now looks bleak. Or, at the very least, deeply uncertain with investors being warned to pre- pare for a greater dose of instability ahead.

A big catalyst is the repeat of Donald Trump versus Joe Biden for president in November, threatening to create a huge level of doubt politically, economically and financially.

To emphasise this point, Tina Fordham, a geopolitical risk strategist, has warned that the “prospect of an uncontested result is lower than for any of the past five American elections,” with the possibility of “disputes, re-counts and even a Supreme Court referral highly plausible”.

For Steven Dover, head of the Franklin Templeton Institute, this could well be a cause for concern. “A contested election, much less a constitutional crisis, would presumably have significant short and possibly longer-term implications on how domestic and international investors assess US country risk,” he says.

Underlying dynamics

But one investor has a word of warning on such an analysis. The correlation between elections and volatility can be spurious, says Paul Allison, portfolio manager at Border to Coast Pensions Partnership. “Often it is underlying market dynamics that lead to volatility, such as during the financial crisis in 2008, or the pandemic in 2020, rather than the election itself. The data is somewhat inconclusive when adjusting for these factors.”

Having said that, Allison accepts the unique nature of what 2024 is likely to offer, with all its vicissitudes. “There’s a strong chance that a Trump/Biden rematch would be as – if not more – contentious than in 2020, with a drawn-out post-election process of recounts and contested verdicts possible.”

He is, as an investor, therefore set for such an outcome. “Our view is that volatility is more likely than not to increase through- out the year, but this is by no means a guarantee.”

White House returns

Allison offers some interesting and deeper insight in terms of US elections and their outcomes. “Over the long term, there is little correlation between which party controls the White House and equity market performance,” he says.

Since 1946 Republicans and Democrats have almost shared presidential control of the White House and over that period equity markets have tended to rise regardless, with the S&P500 producing an annualised return of around 11%.

“Democrats hold a slight edge when it comes to stock-market returns and White House control, but, again, that is more down to the underlying economic and stock market dynamics than political control – despite the respective parties claiming otherwise,” Allison adds.

There is, however, nuance when it comes to control over congress. “In general, stock markets tend to look more favourably on a split congress, where one party controls the senate and the other the House of Representatives, believing that this reduces the odds of any over-reaching legislation or unfavourable policy being signed into law,” Allison adds.

“When either party had control over congress and the White House, stock-market returns were slightly below average, although total control is a rarer occurrence,” Allison says.

Blackrock’s US chief investment officer, Tony DeSpirito, has a similar level-headed analysis when it comes to the run up to the election. “For equity markets, election years traditionally start slow – and volatile – but improve with greater certainty.

For example, once candidates are nominated in the summer and after election day. “The outcome of the election historically has done little to change this pattern, suggesting that clarity is more important than parties or politics when it comes to the broad market,” DeSpirito adds.

And many companies, although aware of the potential problems ahead are keeping calm and carrying on. “While many have dubbed this the most consequential election in decades, that sentiment is not necessarily showing up in company rhetoric,” DeSpirito says.

“So far, we see the lowest percentage of firms discussing the election versus any of the past three cycles, with less than 10% of companies citing ‘election’ in their Q4 earnings calls,” he adds. “Mentions typically pick up as the year goes on, but this is the lowest starting point in recent history. One reason may be that the likely candidates, the current president and a former president, are well known entities, blunting the uncertainty factor,” DeSpirito says.

Trump impact

This doesn’t seem to be creating a high level of uncertainty for investors.

But there are other factors to consider. Some investors have warned of the impact a Trump victory may have from a financial perspective, given that he has threatened to slap 60% tariffs on China, and a 10% tariff on imports from other countries.

This could lead to a trade war, just as the global economy seemed to be going in a positive direction after the devastation wrought by the Covid pandemic.

In addition, analysts at Goldman Sachs also warn that a victory for Trump in November would be bad for European stock markets. In an investor note, the asset manager behemoth wrote: “Europe equities are sensitive to international trade, geopolitics and economic policy uncertainty.”

It added that the prospect of tariffs on exports to the US – a Trump proposal – would be a “significant negative” for European stocks.

This confirms an extremely troubling picture for investors, and one beyond just America. That said, it should be noted that stock markets did rise during Trump’s first term.

But it can safely be said, and this is surely a key point, that the backdrop is now different – especially given the additional and growing concern over the US deficit.

But the equity risk premium – a measure of relative stock pricing versus bonds – looks more compelling for the equal-weighted S&P500, sitting near the market’s long-term average.

“This implies the need to look beyond the mega-cap stocks that have been dominating the widely cited market-cap-weighted index to source attractively priced names with good long-term prospects,” DeSpirito says, indicating that there are investor gems to be found in the “America in trouble” picture.

Then there is the matter of inflation.

In April it rose to 3.5%, dashing investor hopes of an interest rate cut any time soon. This was borne out by the fact that the Fed left interest rates unchanged for the fifth consecutive time and kept its benchmark-borrowing rate at between 5.25% and 5.5%.

Yet the Fed also said that it still expects three quarter-percentage point cuts by the end of the year. But investors are, understandably, already questioning such a stance.

It has also raised questions of investor appeal in America falling behind other geographies, such as Europe and Asia. There is therefore potential trouble in America on some fronts.

A path less travelled

And it is the challenge from other geographies that pose a clear test for the US in investment terms. Its heightened strategic rivalry with China is always a primary focus of global markets.

“Tensions between Washington and Beijing have intensified on multiple fronts, including struggles over trade, technological dominance, cybersecurity, political ideology and relations with Taiwan,” says Thornburg Investment Management port- folio manager Joe Salmond.

And he adds, this leaves opportunities for investors, but not for the US. “If other conflicts leave Western countries spreading their military resources thin, it could create opportunities for China and other countries to push their agendas more aggressively,” Salmond says.

With the trouble in America, Salmond believes investors should remain nimble and focus on diversification. “One rarely wants to put all their eggs into one basket, but it is particularly ill-advised when that basket is wobbling so precariously,” he says.

“Diversification is there for when things suddenly and unexpectedly go wrong,” Salmond adds. “And when more things could potentially go wrong, as we think is the case now, diversification is more critical than ever.”

To build diversity in a portfolio, one needs to look where others are not, Salmond suggests. “A fundamental aspect of our research process is looking for divergences on a company, sector or country level to find companies performing differently than the rest of the market. This strategy is integral to uncovering overlooked, under-appreciated and under-valued opportunities and helps us maintain a well-balanced portfolio with a diverse array of idiosyncratic risks and rewards.”

And with the trouble in America, almost inevitably, leads to other nations becoming more appealing within this undervalued scenario. “This dovetails nicely into two of the biggest topics in international markets today: China and Japan.

“First on China, where in an act of magician-like handwaving, most investors have managed to behave as if the world’s second largest economy no longer exists from an investment perspective,” Salmond says. “We firmly believe that entirely dismissing China is a mistake.”

Sitting at the other end of the investor sentiment spectrum as an alternative to America is Japan, which had long been out of favour with investors due to its sluggish economic performance for more than a generation.

“However, meaningful policy changes in Japan – such as a sharper focus on corporate governance and business profitability – have sparked a shift in the corporate and economic land- scape,” Salmond says.

“While other investors have largely neglected Japan over many years, our team has remained committed to researching and uncovering hidden opportunities there,” Salmond says. “This approach has enabled us to invest early in the best opportunities at discounted prices, positioning us for meaningful gains.”

Green election

But investors don’t need to take a stark turn away from the US within the “trouble in America” narrative. There are also investor implications to be found in the US leading up to, and surrounding, the election, DeSpirito says. “The clearest may be among companies tied to ‘green’ initiatives if the election were to bring a party change in the Oval Office that could affect some of the regulation and incentives tied to the energy transition,” he says.

“The election mentions among companies engaged in these businesses may be an indication of that concern,” DeSpirito adds. “Importantly, this would not change our long-term outlook for fundamentally strong businesses in this category, particularly those with global operations. It could even present a buying opportunity in some cases if prices were to adjust downward on election worries.”

In addition, healthcare companies, which are typically in the crosshairs of political machinations, have had little to say thus far. “Potential candidates are not campaigning on drug pricing or ‘Medicare for All’ as in prior cycles,” DeSpirito says.

Which in turn, leads to opportunities. “This muting of political risks further supports our favourable outlook on this versatile sector – one with defensive characteristics as well as attractive growth prospects amid increasingly brisk innovation, such as the GLP-1 ‘diabesity’ drugs,” DeSpirito says.

Yet any nod to the trouble in America narrative comes at an interesting moment, especially given that bolstered by the latest financial results, investor sentiment on US earnings rose to a two-year high of 7% – the first positive reading over that period – according to S&P Global’s latest Investment Manager Index survey.

“Investor concerns over a reduced stimulus to equities from fewer central bank rate cuts have been trumped by expectations of improving corporate performance on the back of brighter economic prospects,” says Chris Williamson, executive director at S&P Global Market Intelligence.

So investors are far from seeing only bad news when it comes to America. Is there then a case to say that the US market is, in any way, exceptional? One view is that it’s just the tech giants – the constantly mentioned magnificent seven – making it exceptional.

According to the Blackrock Investment Institute the growing heft of sectors with high-quality earnings and AI-exposed names in the S&P500 – notably tech and telecommunications – is helping stocks overcome the drag of higher interest rates.

Expectations of a fall in US equities appear likely for other reasons. “The current high equity-market valuations – above long-term norms – and earnings – higher than long-term averages, suggest that overall equity market returns are likely to be lower over the next five-to-10 years than they have been over the first quarter century of this millennium,” Dover says.

The party or parties in power could make matters worse or perhaps better, of course. “But the prospects for sustained strong equity gains may not be favourable no matter who wins,” Dover adds.

Whatever shape the election in America takes, there will be investor risk ahead. “Should a divided government in 2025 lead to the recurring threat of government shutdowns and a potential default, that would have adverse impacts on risk assessment,” Dover says.

And Paul Allison also notes risk as a factor in the run up to the US election: “It’s always a good idea for investors to be alert to investing risks, be those risks to market drawdowns or increases in volatility.

“The general perception is that markets are more volatile in the run up to elections – investors, after all, dislike uncertainty.”

Comments